For you Rust Belt boosters, Sandusky aficionados, history buffs, arts lovers, and education champions … I’m so pleased John Kropf agreed to answer my questions about his fascinating historical memoir …

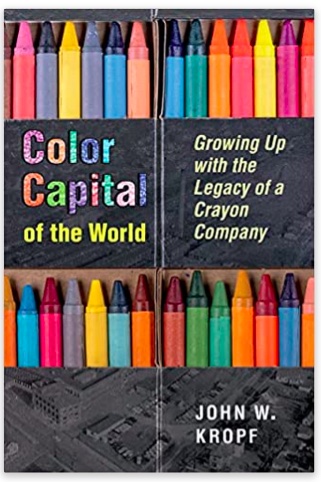

John Kropf is the author of Color Capital of the World: Growing Up with the Legacy of a Crayon Factory (University of Akron Press, 2022). Color Capital provides a history of the crayon through the build, boom, and bust of the American Crayon Company. Readers will come away feeling a greater appreciation of the human story behind the crayon and the Ohio town that produced more crayons and paints than anywhere else in the world. Melissa Scholes Young, author of The Hive and Flood, described it as a “delightful and engaging read.” Kropf’s earlier work, Unknown Sands: Travels in the World’s Most Isolated Country, was praised as a fascinating narrative bound to hook adventurers. His writing has appeared in The Baltimore Sun, Florida Sun-Sentinel, The Washington Post, the Middle West Review, and elsewhere. Kropf was born in Sandusky and raised in Erie County, Ohio. He works as an attorney in Washington, D.C., area.

John, multiple lines of your family came together to make the American Crayon Company, begun not long after the end of the Civil War. Your grandmother was the one to tell you the stories of the company. In Color Capital, you write that it was at her “Sunday afternoon dinner table with its white tablecloth and real silverware [where it] felt almost like I was receiving a sacrament in church. I was hearing the gospel of the crayon.” You also write, “Crayons were my birthright.” What did it feel like to have this legacy, as a child, and then see it decline and finally disappear?

Be careful of the stories you tell your children! My grandmother’s stories and the magic of crayons was a powerful combination for a young child. Crayons were somehow different–not like ball bearings or rolls of finished steel. Crayons were something easily understandable and exciting for a kid. And from a kid’s perspective, I thought there must be a way to keep it going. As I mentioned in the book, I desperately wanted to find a way to be part of it, but by the time I entered high school, I realized the company had been sold from the founding families and I could see the decline of the company coming. Maybe the hardest thing was decades later reading the stories in the Sandusky Register that the abandoned factory building had been neglected for so long it was falling into ruin. It was kind of like seeing an old family relative with no one to take care of them. There’s a head-heart issue going on–your head knows it is the natural end of a business but your heart reacts to mourn the loss.

I am a big crayon fan now! I never gave so much thought to the importance of crayons. One very important point you make in the book is that this was something made and built for children. I was fascinated to learn that the crayon movement and the kindergarten movement (pushed by German immigrants) coincided. Yes, there were crayons made for train workers, carpenters, and other industries, along with crayons made for artists; but the bulk of crayons made were made with children and their art and education in mind. In your research, what was the thinking behind these Germans interested in putting color sticks in children’s hands? What a shift after a time of war, I would think, this time of color. That shift in the company from the “rugged utility of blackboard chalk and industrial markers” to “pure creativity and imagination of children and artists.” What do you make of that?

Yes–it was an exciting time in education. The crayons that American Crayon Company and others, like Binney & Smith, created in the first part of the 1900s were practical and inexpensive. American Crayon even made “penny-packs” that had different pictures on the back of the package to encourage children to color. We think of computers in a similar way being introduced in the 1980s in schools and colleges. The introduction of affordable color crayons to young children was revolutionary. Coloring contests in schools were a big deal, where the winners could earn prizes and national recognition. American Crayon even developed a magazine written by educators, called Everyday Art, to help teachers with coloring projects.

It goes hand and hand with the art education of young students that Sandusky was a pioneer in secondary public education, as one of the first towns in Ohio to develop a public high school. From your research, can you tell us what made Sandusky an education leader? What were the conditions that made that possible?

I think some of the conditions go all the way back to Ohio being part of the Northwest Territories. The Northwest Ordinance that carved out Ohio and other Midwest states mandated public education among its first articles. The emphasis on public education created a demand for new and innovative teaching techniques–the kind that drew one of American Crayon’s founders, Marcellus Cowdrey, to Sandusky to become its first superintendent of schools. Marcellus had been educated at a teaching academy in Kirtland, Ohio, and he emphasized good penmanship as a critical skill to learning. From his start in Sandusky, Marcellus wanted to ensure his students would have practical effective means of practicing their penmanship, starting with chalk on the blackboard. His techniques helped create Sandusky as an innovative center for public schools and set the stage for better writing implements.

Your book helped me learn about Sandusky from the ground up, as “The Color Capital of the World,” as a relative of yours said the city was known. Sandusky is also known for its gypsum mines. I had no idea what gypsum was, until I read this, and I certainly didn’t know it was used to make crayons (among other things). You detail the development of the formula for crayons (slightly different across brands). I’m thinking the crayon recipe likely ran parallel to other industrial recipes. Can you give us a sense of what else was being developed in the time period that this development is happening?

Researching the book, I learned that gypsum deposits in northern Ohio were a vestige of glaciers. The deposits are found in silts and clays in the beds of former glacial lakes. William Curtis, the crayon company’s inventor, had access to the gypsum through his brother-in-law, John Cowdery, who ran a local outdoor nursery located near an abandoned quarry with a deep pond in it. I like to think the American Crayon Company was truly connected to the land and water of Ohio and nearby Sandusky Bay.

In your book, you also give readers a history lesson of the greater area, going back to the end of the Revolutionary War. At the time, Sandusky was part of the Northwest Territories, created in 1787 by congressional ordinance. This fascinating piece of history I didn’t know: “…the ordinance did something the U.S. Constitution had not been able to do—explicitly ban slavery throughout the territory.” That fact, along with the fact that Canada is just across Lake Erie made Sandusky a “critical link” on the Underground Railroad. Can you tell us another historical fact of the area, one that maybe didn’t make it into the book?

Sandusky had been at the center of innovation in the 1800s. I mentioned in the book that the first chartered railroad west of the Allegheny Mountains was started in Sandusky, The Mad River and Lake Erie Railroad. The railroad created a demand for skilled mechanics and engineers and that is what attracted my great, great grandfather, Jonathan Whitworth who emigrated from England. It was his son who was one of the founders of the crayon company.

It’s also worth mentioning that at the very end of the 1800s Sandusky begin building segments of an electric interurban railway that later merged Lake Shore Electric Railway that connected numerous small communities with Cleveland, Toledo, and Detroit. The was the second railway of its kind in the country. Coincidentally, Thomas Edison had been born in Milan, Ohio, in Erie County just 10 miles south of Sandusky.

The American Crayon Company, at its peak, employed about 500 factory workers, salespeople, and staff across several offices around the country, with the factory in Sandusky. What was Sandusky like in this heyday?

I don’t know if it was the heyday, but as a child in the 1960s, Sandusky, like so many other small and medium sized towns, still had a thriving downtown shopping district including a department store. It was in the early 1970s that the Sandusky mall was built south of town and the downtown followed the pattern of so many others with stores closing. What’s ironic is now many of these malls are struggling to survive or closing. I’d like to think people truly value the downtown experience of a real town.

There are glossy, full-color photos in the center of the book that really are compelling. Can you talk about your favorite photo(s)—one that was a challenge to get, maybe, or one with personal significance?

I suppose the one that I’m partial to is of William Curtis in his Union Army uniform holding a sword. He has the most intense, hardened look on this face. I try to imagine what he must have been thinking at the time.

Your personal connections are what makes this a memoir, even more than a fascinating history of a place, and I most like when you consider how the generations before you might have felt. Your great-grandfather went from grocery clerk at age fifteen to a bank president to American Crayon Company president in thirty years. This is American Dream kind of stuff. You went to law school and have a good career. What do you think he would say if he time-traveled to the here and now to see you?

I’m not so sure I could imagine what he would say or think. I know, I’d have many questions for him about how he learned about business and how he took a risk with financing the crayon company.

I found the parallels you draw in the book between Sandusky and your personal journey really illuminating. You write of the difficult times in your family, when over the course of a few years, your grandmother died, and then your parents divorced and you moved with your mother to a nearby town. You say, “The outside world in the mid-seventies also seemed to be in decline…Familiar stores in downtown Sandusky were closing and land was being cleared south of the town for the new Sandusky Mall.” (If that’s not a death-knell for our historic downtowns, I don’t know what is.) Do you think these parallel declines helped push you to go away for your education and career?

I didn’t think about it consciously. I suppose I didn’t see the kind of opportunities that I wanted in my future with so many businesses closing. The metals company that my father worked for in Sandusky was bought out and he was transferred out of state. I even worked there a summer in college but that foundry was later shuttered and demolished. I suppose I was lucky enough to have very supportive and encouraging parents who had lots of books in the house that exposed me to many different places and ideas. Pursuing a law degree was what I felt was a form of security in reaction to the insecurity I saw around me.

After college, you made the same journey your grandfather did 70 years before, across the U.S. from Sandusky to Pasadena, California, where he had American Crayon offices. Why did you make his trek? And what was the most important thing you learned from yours?

I think having an adventure before I stepped into the professional world was something I had to do and it was also a way for me to connect with my grandfather who had just gotten out of the army after World War I [when he made his trip]. One of the parallels that I loved was that we were both 26 when we made our trips. I was preparing to start my first job as a lawyer and he was preparing to go into the family business at American Crayon. I even hope to write a book about his trip and my trip, together. I published a magazine article out of it and I still haven’t given up the thought that I could do a book on our parallel trips, me following in his footsteps.

In 1988, you moved to D.C. and started your professional journey. Fast-forward to your book. Why did you write it when you did? What was the impetus?

In short it was loss. In 2014, I first read about the abandoned American Crayon Company in Sandusky and the long drawn out wrangling over its demolition. A short time later, I lost both my mother and sister who were part of that crayon story. Two years in a row, I returned to Oakland Cemetery in Sandusky, both times to bury them next to the founding family members of the crayon company. My father also died about this time and I felt I was the last one standing that had the stories I wanted to share.

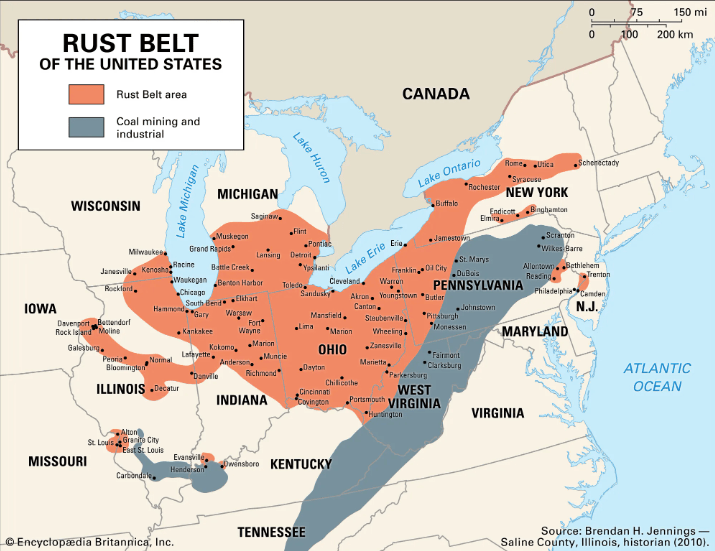

You talk about Sandusky as a younger sibling of Cleveland to the east and Detroit to the west. I’m reminded of the smokestacks our native cities have in common. You’ve been taking your story to the Cleveland area and other neighboring places. I’m guessing you’re hearing some similar stories of the rise and fall of industry and small manufacturing in other places. What’s the reception been like?

It seems like a natural fit to me that the story of an innovative and successful industry hits its bust. People understand that story in Cleveland, Akron, Toledo, Detroit, and many of the other Midwestern industrial towns. In researching my book, I read a lot of other memoirs from these cities and understood their build, boom, and bust stories.

You write, “…under the monochrome, gray skies of northern Ohio, was an explosion of color.” Northern Ohio, along the lake, is known for its overcast skies. I think it’s romantic but it can take some getting used to. I’m imagining crayons and colors mean so much more to children who don’t get to glimpse the sun from November through March. (That might be an exaggeration.) Can you tell us a personal childhood crayon story that didn’t make it into the book?

When I wrote that, I kept thinking about the contrast between the grayness of northern Ohio in the winter and the spectrum of brilliant colors being produced on the inside of the factory, and how the colors were being sent out to the world to help brighten things up.

The fall of the American Crayon Company mirrors the decline of manufacturing and industry across the Rust Belt. What did it mean for Sandusky when the company was sold and the manufacturing moved to Mexico? What did it mean for you, personally, as a son of Sandusky and a legacy child of the American Crayon Company?

It seemed like adding insult to injury in ending such a great company. When I spoke at the Sadusky library about my book, there were union members from the factory who told me they refused to train their Mexican counterparts and that scabs had to be brought in to try to train them on the antiquated and delicate equipment. When the venture in Mexico failed within a year of its relocation, it seemed like there was some sort of small irony at play–equipment taken from the American Crayon Company transported outside the country was never meant to operate anywhere else but Sandusky, Ohio, U.S.A.

What has it meant for you to see Sandusky come back again, the action on the waterfront, new condos where old industry was. What are your favorite places to go when you go back? How about your favorite local beer or other beverage? And, if there is one, a particularly Sandusky meal you never miss?

It’s actually very inspiring to see Sandusky making this transition. It will never be the same type of manufacturing center it was but I don’t think that could ever come back. What I’m pleased to see is the preservation of some of its great old limestone buildings and city and business leaders looking ahead to capitalize on Sandusky’s location on the waterfront along with nearby Cedar Point Amusement Park and Sandusky’s other historical sites and markers like the Underground Railroad.

Favorite places are the downtown waterfront, including a look at the coal docks that are a prominent feature of Sandusky’s skyline. Other stops are the Sandusky Library and Oakland Cemetery and newer spots like the rooftop bar of the Kilbourne Hotel that overlooks Sandusky Bay.

As far as food goes, whenever I’m in town, I always stop for a Lake Erie Perch sandwich.

Be sure to follow John on Twitter (@JKropf)–especially if you’re in Ohio. His pinned tweet lists his author events, a few of them next month!

Like this interview? Comment below or on my FB page. And please share with your friends and social network.

Are you a Rust Belt writer interested in seeing if an author interview or book review of yours might be right for Rust Belt Girl? Pitch me through this site’s contact function.

Check out my categories above for more interviews, book reviews, literary musings, and writing advice we can all use. Never miss a post when you follow Rust Belt Girl. Thanks! ~Rebecca